Archaeology A to Z

From aerial photography to zooarchaeology, and taking in everything from isotope analysis to stratigraphy, this A–Z offers a deeper look at the tools, techniques, and terminology that archaeologists use to understand the past. Whether it’s the science behind how we date ancient materials, the methods used to reconstruct past environments, or the specialist vocabulary you might come across in excavation reports, this guide is designed to open up the fascinating world of archaeological practice.

If there’s an archaeological term, method, or concept you’d like us to add to our A–Z, we’d love to hear from you—just get in touch!

Aeriel photography

Archaeologists use aerial photographs to spot archaeological sites from above. They show archaeological sites as cropmarks and earthworks.

Cropmarks occur where there are archaeological features, such as walls and ditches, underneath where a crop is growing. For example, greener healthier crops grow above ditches where there is more soil depth. The result is a plan (or birds-eye) view of the layout of features across a site.

Earthworks are banks, ditches and mounds of earth and stone. They cast shadows, which can show up in aerial photos.

Aerial photos are particularly useful because they often show more of an archaeological landscape than is visible from the ground.

Alum industry

The alum industry has been described as “the first chemical industry”. Alum is a chemical made up of aluminium sulphate with either ammonia or potassium sulphate. It was used for a number of things such as fixing dyes to clothes, tanning leather, and in Roman times it was used for purifying water. Prior to Henry VIIIs break with Rome, alum was mostly imported from Italy, with the Vatican controlling most of the world supply; this supply was stopped after the Reformation. With wool being the principal industry in Britain, another source of alum had to be found; most of the production of alum took place in Yorkshire, both on coastal sites and further inland. There are examples in Dorset and in Lancashire.

The alum process was a long one; firstly shale had to be extracted from quarries and burned to separate the alum from the quarried shale. This burning could take months and sometimes up to a year to complete. The burnt shales would then be leached in large tanks of water to create a liquid called aluminium sulphate. This would take place in several stages, through a series of tanks which would remove impurities and concentrate the liquid aluminium sulphate further. It was then transported to an alum house where it was boiled over a coal fire. To create the alum crystals a source of potassium (such as potash or burnt seaweed), or a source of ammonia (such as urine) was mixed with the aluminium sulphate. It was then left to cool.

The last alum works were closed in 1871. Many were located at the coast because it provided easy access to quarrying shales from cliff edges, as well as easy transportation for resources such as coal, seaweed, potash and urine. Many remains such as alum houses and sluicing tanks can still be seen, as well as jetties and wooden staithes which would have been used by boats associated with the industry.

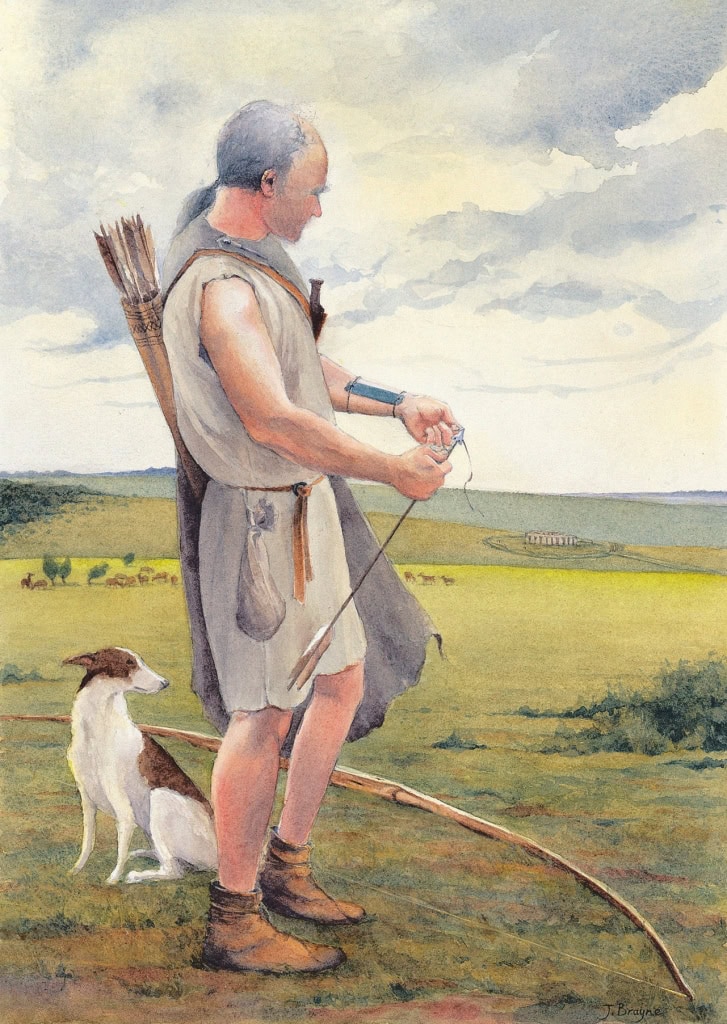

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period of prehistoric archaeology which falls between the Neolithic and the Iron Age.

In northern Europe, the Bronze Age is considered to be the period between about 2300 and 700 BC.

It was during the Bronze Age that metal began to be widely used across Britain to make tools, weapons and other objects. It was also during the Bronze Age that farming became more intense, with communities becoming bigger than those of their earlier Stone Age ancestors.

Conservation

Conservation of archaeological finds basically means looking after them!

Conservation aims to make sure that objects do not decay after they have been excavated. Conservation includes the study, preservation and restoration of finds. Different objects need to be conserved differently. For example, wooden objects need to be cared for very differently to metal objects.

Dendrochronology

Dendrochronology is also called tree-ring dating. It is a way of dating a piece of wood, based on the size and pattern of its rings. It works because living trees add a ‘growth ring’ to their trunk and branches every year.

The size of the rings depends on the conditions where the tree is growing. In dry years the ring is thin, whereas in wetter years the ring will be thicker. Trees of the same type growing in the same region will have similar patterns of tree-ring growth. Experts have created master tree-ring profiles for different regions showing the pattern of thin and thick rings (a bit like a barcode!). When pieces of timber of an unknown date are found, they can be compared to the master profile. By matching up the order of thin and thicker rings, the piece of timber can be dated!

Image attribution: Adrian Pingstone © WikiCommons

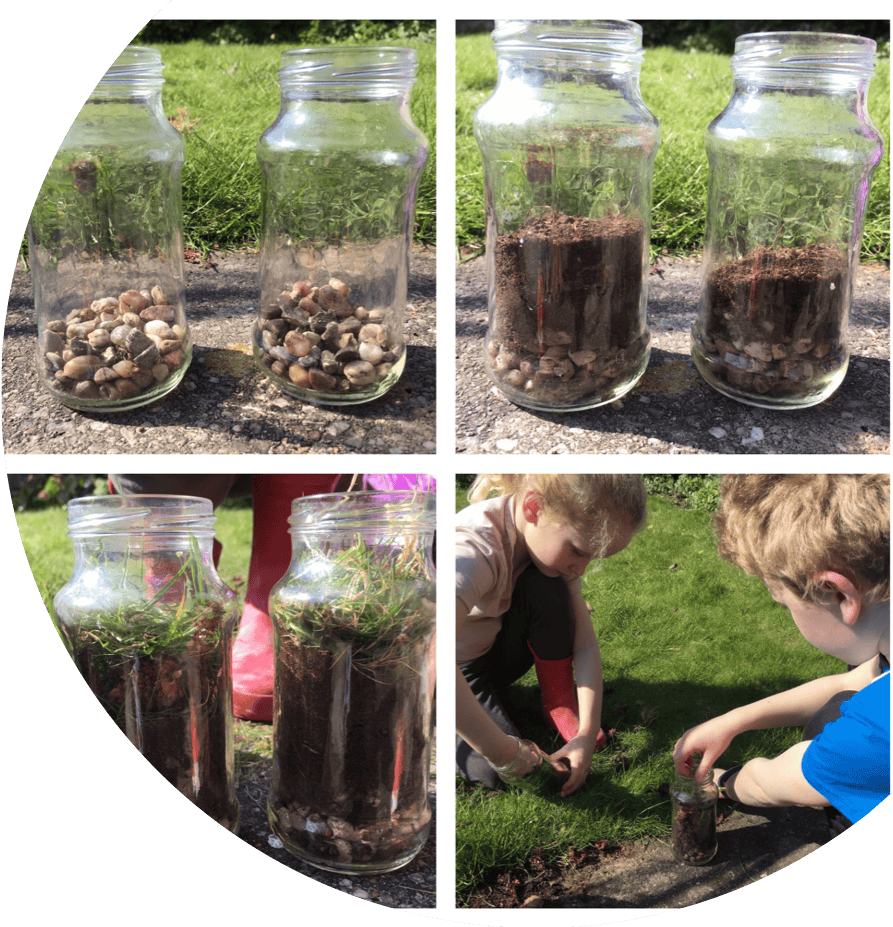

Experimental Archaeology

Experimental archaeologists try to understand how our ancestors lived.

Experimental archaeology is the study of ancient technologies and activities by recreating them through hands-on experiments. By building replicas of ancient tools, buildings, or vessels and testing how they were made and used, archaeologists can generate and test hypotheses about past cultures. This approach helps provide a deeper understanding of how ancient people lived and solved problems.

Fieldwalking

Fieldwalking is used to map where archaeological objects are found across the surface of ploughed fields.

There are two main types: line walking and grid walking.

Line walking is where a group of fieldwalkers walk alongside each other spread across the site. They walk forwards in a straight line, collecting finds (such as worked flint or pottery) as they go. Each ‘line’ is split into sections usually called ‘stints’; finds are bagged up depending on which line and stint they were found within.

In grid walking, the survey area is split into squares. Each fieldwalker is given a square to search for finds in a set length of time. Finds are then bagged up by grid square. Both these methods allow archaeologists to map where there are find ‘hotspots’ across a site. The pattern of finds might then help them to decide where to place their trenches in an excavation.

The YAC members were given a brand new field and a new mystery to investigate: does the reputed Roman road really run through this field? © Pontefract YAC

Fish hully

Fish hullies could be considered a version of refrigeration before fridges were invented. Once fish and shellfish were caught, there had to be a means of keeping them fresh and in some cases this meant keeping them alive. Some places used fish hullies; in Northumberland these are also known as Bratt Holes. They are pits cut into the rocks which were submerged at every high tide, to provide fresh sea water, where fish and shellfish could be stored until they were transported. Examples of these have been found at South Landing in Yorkshire and Beadnell in Northumberland.

The example at Beadnell was cut into the rocks and has a recess to which a wooden lid can be fixed so that the fish did not escape at high tide. Other examples are at Robin Hoods Bay in Yorkshire and Cresswell in Northumberland. Fish hullies tend to be found in the North-East and Yorkshire and appear to only have been used in areas where no deep water harbour was present.

Fishtraps

Fishtraps, sometimes known as fish weirs, are a method of coastal fishing. Fishtraps or fish weirs use man-made barriers to guide fish into baskets; sometimes this works in conjunction with the tide. There is evidence of Mesolithic fishtraps but this method of fishing was being used until relatively recently, such as at Cleethorpes, where fishtraps were used into the 20th century. A majority of fishtraps are located in the intertidal zone. Prehistoric and Roman fishtraps are rare and this is mainly due to sea level rise. It means that very low tides are needed to see them because much of the time they are covered by water even at low tide. Some of the medieval examples are associated with monasteries or manors.

Fishtraps are usually made of wood but some stone and metal examples are known, such as the stone example at Teifi Estuary in Dyfed. Fishtraps are usually “V” shaped structures, with the open end of the “V” facing seaward. When the tide comes in, so do the fish. The barriers guide the fish into a wattle basket or net located at the point of the “V”. The shape of the fishtrap is constructed of timber stakes and then the barriers are usually wattle hurdles, weaved from willow or hazel. Archaeologically, stone fishtraps are hard to recognise but are more durable than wooden examples. Wood fishtraps are usually identifiable by the remains of upright stakes, in the “V” shaped formation. It is less common to find the wattle baskets and hurdles but some examples have been found, for example on the Thames and the Severn.

Fossil

Fossils are the preserved remains of animals and plants. They are usually very old and not made by people. For this reason, archaeologists don’t actually dig for fossils. Archaeologists are interested in the study of the past and concentrate on material culture (many periods studied by archaeology pre-date written records) to understand early societies. Sometimes we do find fossils buried in archaeological contexts though: even people in the past might have liked their unusual shape and maybe they picked them up as keepsakes!

Geophysics

Geophysics studies the physical properties of the earth to find possible archaeological features without digging. There are three main types: resistivity, magnetometry, and ground penetrating radar.

Resistivity measures the resistance to an electrical current between two probes in the soil. Walls and buried features have high resistance, and pits and ditches have low resistance.

Magnetometry measures the differences in magnetic fields of different soils and features. Magnetometry is good for finding metal-working sites, hearths and fireplaces, and rubbish pits.

Ground penetrating radar sends electromagnetic waves into the soil and records variations in the reflected return signal caused by buried features.

The data collected by geophysics are used to create computer pictures, which can show up where archaeological features are underneath the ground. Geophysics is therefore used before an excavation to try and decide the best places to dig.

Historic Environment Record

H is for Historic Environment Record

Every local council across the UK has an Historic Environment Record (HER).

HERs hold information and photographs on known archaeological sites, finds, landscapes, historic buildings and the historic environment. They are updated regularly with new information provided by professional archaeologists, historians, researchers, metal detectorists, and even YAC clubs!

HERs are a brilliant source of information for anyone interested in the archaeology and history of their local area.

To find out more about your local HER, contact your local council, or visit www.heritagegateway.org.uk and click on ‘Historic Environment Records’ on the menu on the left-hand side of the page.

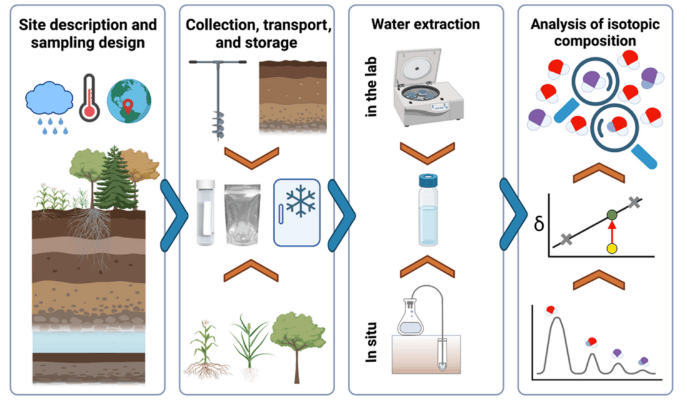

Isotopic analysis

I is for Isotopic analysis

And now for the sciency bit! All the elements found in the Periodic Table – such as hydrogen and oxygen – are made of atoms. Every normal atom is made up of a specific number of protons, electrons and neutrons. Isotopes are atoms of the same element with a different number of neutrons, which means they have slightly different weights.

Isotope analysis uses the oxygen isotopes in human teeth to work out where people come from. It works because nearly all of the oxygen that goes into building bones and teeth comes from the water that was drunk during childhood (water is made up of the elements hydrogen and oxygen). The water that we drink comes from rainfall, and the type of oxygen isotopes in rainfall depends on the local natural environment. Water in warm climates has more heavy isotopes (so-called ‘oxygen 18’) whereas water from cold climates has more light isotopes (‘oxygen 16’).

Oxygen isotope analysis of the teeth from skeleton of the Bronze Age “Amesbury Archer” found more oxygen 16 isotopes. Archaeologists were therefore able to work out that he came from somewhere with a colder climate than we find in Britain today, possibly central Europe!

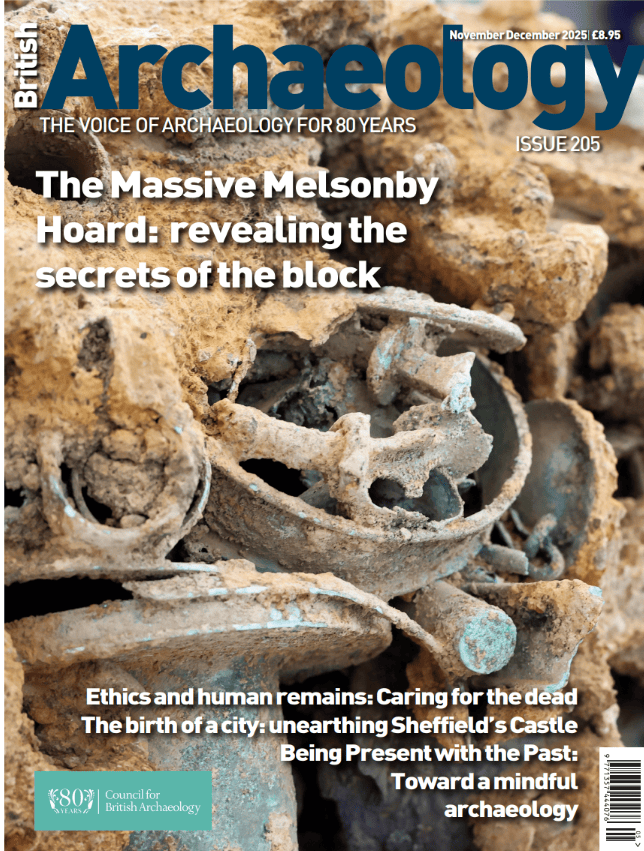

Journals

Lots of archaeological research is published in journals. Some are aimed at the general public, such as the Council for British Archaeology’s (CBA) British Archaeology, whereas others cover specific periods or regions.

Check out the CBA’s British and Irish Archaeological Bibliography. It lists over 2,200 different journals and gives brief information about the articles included in them.

Knapping

Flint knapping is a form of experimental archaeology. It is the shaping of flint into stone tools and arrowheads, as used by prehistoric peoples.

There are different techniques involved. Hard hammering is where cobbles of hard stone are used to break off large flakes from the flint core being worked. Pressure flaking is the final stage of knapping; it involves removing thin flakes along the edges of a tool to make it into its final shape and to sharpen it.

Landscape Archaeology

Landscape archaeology is the study of how people have used the environment around them.

There are two main strands to landscape archaeology: description and interpretation.

Description involves mapping archaeological sites and features over wide areas to try to work out their sequence and relationships to each other.

Interpretation focuses on the use of space by past communities and how they used the world around them.

Landscape archaeology is responsible for encouraging archaeologists to look at much bigger areas rather than concentrating on individual sites.

Monuments

The word monument is basically used for any large man-made structure of archaeological interest!

Monuments can include: buildings, tombs, monoliths, stone circles, mounds, statues, temples, and churches.

Neolithic

Neolithic means ‘new stone age’. It is a period of prehistoric archaeology. In northern Europe, the Neolithic dates from 4000 BC to 2300 BC.

It was during the Neolithic that people first started farming, instead of hunting and gathering. Neolithic people used flint and stone to make tools, and some of the first pottery was made too. Neolithic peoples were also great builders. They constructed huge henges and stone circles, and began to build more permanent homes.

Osteoarchaeology

Osteoarchaeologists study human bones discovered during an excavation.

Osteoarchaeologists look at the archaeological context or the type of grave, the position of the body, and any associated artefacts or grave goods. They analyse bones and try to work out whether skeletons are male or female, and they can even work out how old a person was when they died.

Osteoarchaeologists also look at how disease, diet, and trauma affect bones.

Post-excavation

Post-excavation happens after the fieldwork part of an excavation project has finished. It includes analysing the data collected on site, preparing the excavation archive of drawings and photographs, and producing a report about the discoveries made during the dig.

During post-excavation, experts such as osteoarchaeologists, pottery specialists, and environmental archaeologists might be asked to look at specific finds – such as human and animal bones, pottery, and soil samples – made on site and produce expert reports.

Questions

Archaeology is all about questions – and trying to find answers!

The types of questions that archaeologists try to answer include:

- What was this ditch for?;

- How old is this building?;

- What did people living in this area eat in the past?; and

- What was this object for?

Answering archaeological questions can be very difficult; it’s a bit like trying to do a jigsaw puzzle without all the pieces and without a picture of what the finished jigsaw should look like!

Radiocarbon dating

In archaeology, radiocarbon dating can be used to date objects made of organic materials, such as wood or leather, plant remains, and human and animal bones.

Radiocarbon dating works by measuring how much Carbon 14 (a type of chemical) is in an organic object. All living things absorb Carbon 14 until they die. The Carbon 14 then starts to decay. It does so at a known rate. By measuring the Carbon 14 that is left in an organic object, it is possible to work out how old it is.

Radiocarbon dating will also enable osteoarchaeologists to work out how long ago a person died.

Salt pans

Salt has always been an important commodity. Prior to canning and refrigeration, to preserve and store food it had to be dried, smoked or salted. Salt was also used in the past for tanning, cloth dying and for glazing pottery. In the UK, salt was originally made from either using sea water or inland brine springs. The archaeological evidence for salt making can be found dating as far back as the Bronze Age, with the earliest evidence being found at South Woodham Ferrers in Essex. Place names can give clues to a past salt industry, for instance Saltfleet in Lincolnshire but also places ending in –wich can denote a connection with the salt industry, such as Droitwich.

One of the simplest ways to extract salt was via evaporation from sea water, which was the process used in sunnier locations, such as the Mediterranean. However, in the UK, this was an unreliable method to produce salt! Solar evaporation was sometimes used at the beginning of the process to help increase the concentration of the brine. These sites became known as “sunworks” and involved a series of shallow saltpans, set behind a sea bank, and fed at high tide via sluice gate. Once the sea water had settled, it was tapped off into a second lower pan and then a third, allowing time in each for evaporation to take place. After each stage, the concentration of brine became stronger.

In the medieval period a different method of increasing the concentration of brine at the start of the salt-making process was also used on the coast. It was called “sleeching” in Cumbria and Lancashire, and “muldefang” in Lincolnshire. It involved washing salty sand from the beach in a trench or “kinch” with sea water. When the solution was tapped, the sand was thrown away, leaving a brine solution with a high concentration of salt.

Once the brine solution was strong enough (following either of the processes described above) it was moved to a tank to be heated. To test if a solution was strong enough, an egg could be used: if the egg floated on top then the brine was strong enough for the next stage.

The next process was to remove the salt from the solution, and this was done through boiling. This was usually done in metal or ceramic pots and the crystals were scooped out as they formed. Ceramic lined pits have been found on prehistoric sites and lead lined ones from the Roman sites. There are two remaining coastal salt extractors, one at Anglesey and one in Maldon, and both still use this process.

Stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is all about what happened when! It is the word used to describe the order of layers or deposits found on an archaeological site. It enables archaeologists to work out how different features and finds discovered on a site relate to each other. Layers that are closest to the present-day ground surface will be younger than those buried beneath, with the oldest layers at the bottom.

Submerged forest

Submerged forests have existed for thousands of years and are dotted all along the UK coastline. They are mostly found in the intertidal zone. They were noticed by Gerald of Wales in the 12th century, whilst recruiting for the Crusades. Gerald attributed these forests to the wrath of God and the Great Flood and were known as “Noah’s Woods”. Samuel Pepys also describes a submerged forest, in his diary entry for the 22nd September 1665, in which he discussed a conversation he had with a shipbuilder, who was building a new dock on the Thames. The first systemic research into submerged forests was done by geologist Clement Reid in 1913. Since then more and more research has been done on these sites.

The forests are usually made up of tree stumps and fallen trunks, which are preserved in the anaerobic conditions of the intertidal zone, which enables good preservation of the wood. They can consist of many different species of tree, including: oak, alder, hazel, willow, and birch. To identify what type of trees are present in a submerged forest, samples of the wood must be taken. The samples are viewed under a microscope to examine the cell structure, which enables researchers to determine what type of species the samples are from. Oak is the only species that can be determined by eye. There can be other indications as to what types of tree may have been in a submerged forest; for instance, the remains of acorns or hazels nuts, or distinctive bark such as that from the birch tree. Dates of submerged forests are usually determined by radiocarbon dating. Oak trees can also be dated using dendrochronology (tree ring dating).

Thermoluminescence dating

Thermoluminescence dating is a complicated scientific way to work out how old pottery is.

All materials are subject to radiation given off by the decay of natural radioactive elements. This radiation is stored as energy within the crystal-like structure of pottery. When pottery is heated up or fired to make it hard, all the previously stored energy is released as a light called thermoluminescence. After heating, the build-up of radiation starts again. This means that scientists can reheat a piece of ancient pottery after it has been excavated and measure the energy that has been stored and released since it was first fired. Older pottery will have stored up more energy; and so basically the higher the measurement of thermoluminescence, the older the piece of pottery.

Underwater archaeology

As the name suggests, underwater archaeology is archaeology under water! It involves the study of archaeological sites and shipwrecks beneath the surface of the water in seas, oceans, lakes, and rivers.

Vibrocoring

Vibrocoring is a way of collecting a long ‘core’ sample of soil or sediment on underwater archaeological sites. It is also used where the ground is particularly wet, for example in bogs, wetlands, and on beaches.

It works by using gravity and vibration energy to pass a long tube into the ground. A vertical sample down through the ground is collected inside the tube, showing the different layers of soil.

Wet sieving

Wet sieving is a way of recovering finds and environmental evidence from soil samples.

The sample is passed through a series of sieves with different sized holes whilst being washed with water. The water breaks down the soil making it easier for it to pass through the sieves. Tiny finds and pieces of environmental evidence such as grain, seeds and shells, along with natural stones and gravel, aren’t broken down with the water and are caught by the sieves.

The material caught by the sieves can then be sorted, removing all the stones and leaving behind any archaeological evidence.

X-rays

X-rays are particularly useful for studying metal objects, where rust and corrosion from being buried can hide decoration, or even make it difficult to see the original shape of an object.

X-rays are sometimes used to examine large or fragile objects, such as mummies or cremation urns, before they are excavated.

X-rays are also used for studying human remains.

YAC

Y is for YAC!

The Young Archaeologists’ Club is the only UK-wide Club for young people interested in archaeology.

YAC’s vision is for all young people to have opportunities to be inspired and excited by archaeology.

YAC started as Young Rescue in 1972, so we are more than 50 years old. Your parents may have been members of YAC when they were younger!

YAC has around 80 local hands-on clubs across the UK where you can get involved with archaeology. You can find your nearest club here on the YAC website in our Join a club section.

In 2015 we were presented with an amazing Europe-wide award called an EU Prize for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Award.

Zooarchaeology

Zooarchaeology is the study of animal remains found on archaeological sites.

Zooarchaeologists look at how people used animals in the past, for example which animals were eaten, which animals were kept as pets, and which animals were used for jobs such as transport or farming.